Noh Theatre

In August 1984, I saw my first Noh play in Nara, the ancient capital of Japan. It was Takigi Noh, performed outdoors on a temple stage. Fires were lit at the start of the performance near the stage's edge, and beneath the benches we sat on, mosquito coils burned. It was dusk, mid-summer, and as the actors in their splendid robes and haunting masks moved in ritualistic dance, I felt my sense of time slip away, and I no longer belonged to the 20th century.

On stage sat 14 performers, one of whom was standing, moving, and dancing while intoning in an ancient language. There was a sense of contemplation, quietude. The deep vowel sounds of the Japanese language resonated within the bodies of the singers. I thought of the marae, of whaikōrero, of listeners gathered to hear a speaker.

It felt as if time didn’t matter. Everything was being considered, and it struck me that it was the sound of Te Reo Māori, the aesthetic of marae architecture, stylised carvings, embroidered cloaks, a single voice singing, a monotone chorus joining and parting—these elements were there too. At that moment, the history of the New Zealand Noh Theatre began with a wish that one day I could create a Noh play that would unite these two worlds.

“The challenge as I experience it is thus: I am not a “European,” being fifth generation Pākehā (the Māori name given to the descendants of the European colonizers of these islands). I am neither Polynesian, the Tangata Whenua or original people of this land, nor am I Asian, the other “forst” people of the Pacific. What therefore is my distinctive New Zealand theatre voice? Is it possible to actualize an indigenous Pākehā Theatre? How is the drama of my social and cultural circumstances going to be founded in an authentic and culturally characteristic theatre practice?”

One evening, in 1983, walking in Manhattan by the Lincoln Centre, I happened upon an outdoor performance made up of excerpts of Kabuki, Noh, Bunraku and Nihon Buyo. The Noh performance particularly captured my imagination. The sounds and images were undemanding yet alluring, and I was compelled by the grace and serenity of the moment. The following day, I returned to the Lincoln Centre Library and found a copy of 20 Plays of the Noh Theatre: Donald Keene. I sat and read, returned the book to the shelf and walked to 6th Avenue to buy my own copy. Eight months later, I was in Kyoto at the Iwakura studio of Noh master Michishige Udaka Sensei.

My first visit to Kyoto in 1984 was the first of what has become four visits, 1984/1987/1993/2007. Each time was unique, even though I undertook basically the same activities, learning shimai and utai (dances and songs) from Noh plays. Each day would be a 20-minute class with Sensei, practice, then immersing myself in the city and its wealth of traditional culture.

Rakiura

The first New Zealand Noh Theatre company production was Rakiura by Eileen Phillipp.

In 1978 a young Japanese woman was discovered living in a cave at Doughboy Bay on Stewart Island. Winter was approaching and the local people became concerned for her welfare as her living conditions were rough and exposed to the Antarctic winds. It was then discovered that she had overstayed her visitors’ visa and local police escorted her to Invercargill where she was taken care of at the Salvation Army Hostel. Her elder brother came from Japan; she appeared before the magistrates court and was deported. In 1980 Eileen Phillipp wrote the first ever New Zealand Noh play based on this incident. Rakiura, Maori for Land of the Glowing Sky. Noh Theatre themes are to do with resolution of spiritual estrangement and salvation of anguished ghosts. In the play Rakiura we meet in the first part the actual woman and she expresses her shame at being discovered. In the second part play we meet the woman in a former life and she explains then why she has come to this lonely place.

Our 1993 production was well received and had the following reviews;

Image Credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-Post02187

“An intriguing and fascinating insight was presented into an ageless and beautiful art form.”

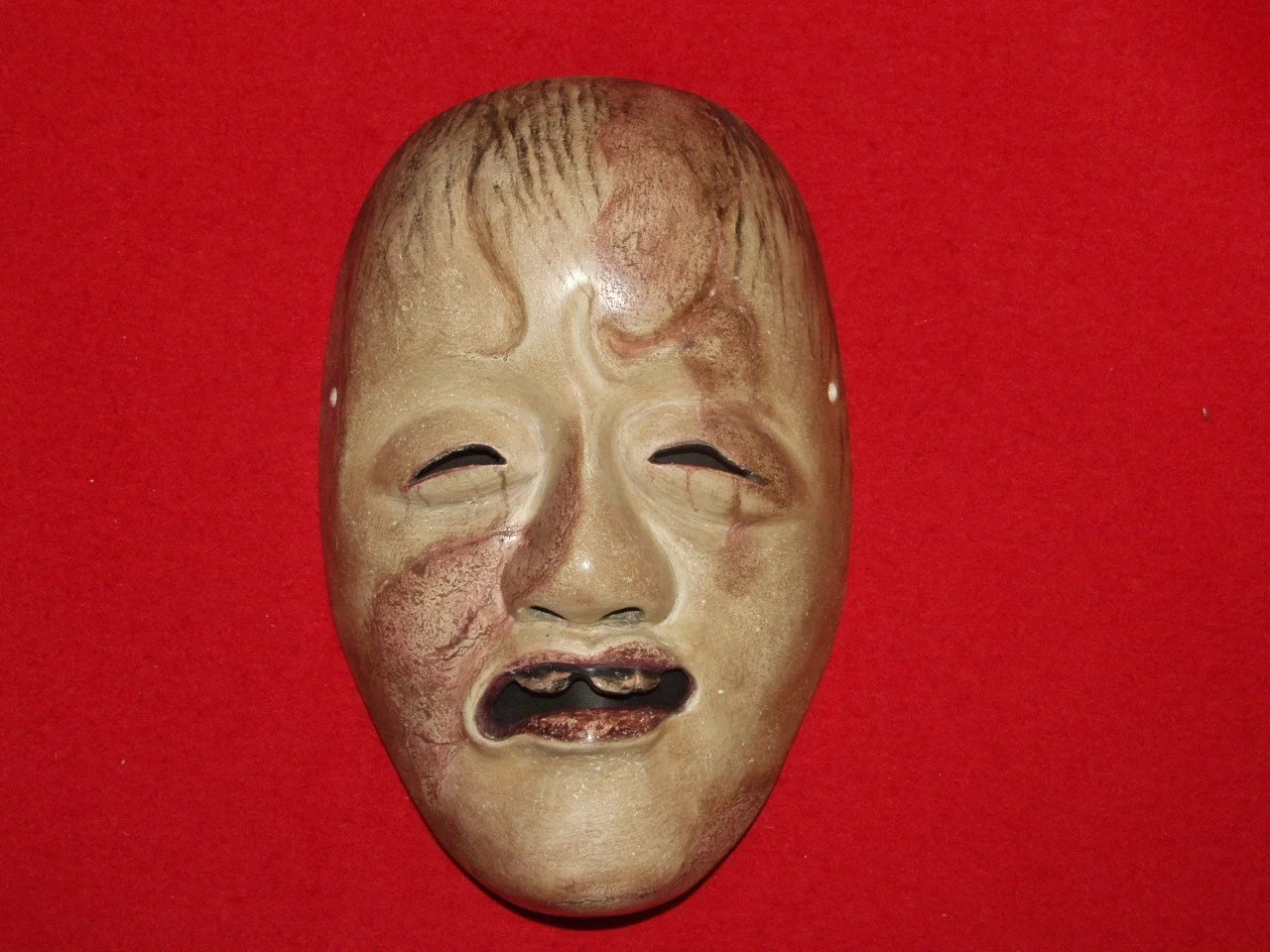

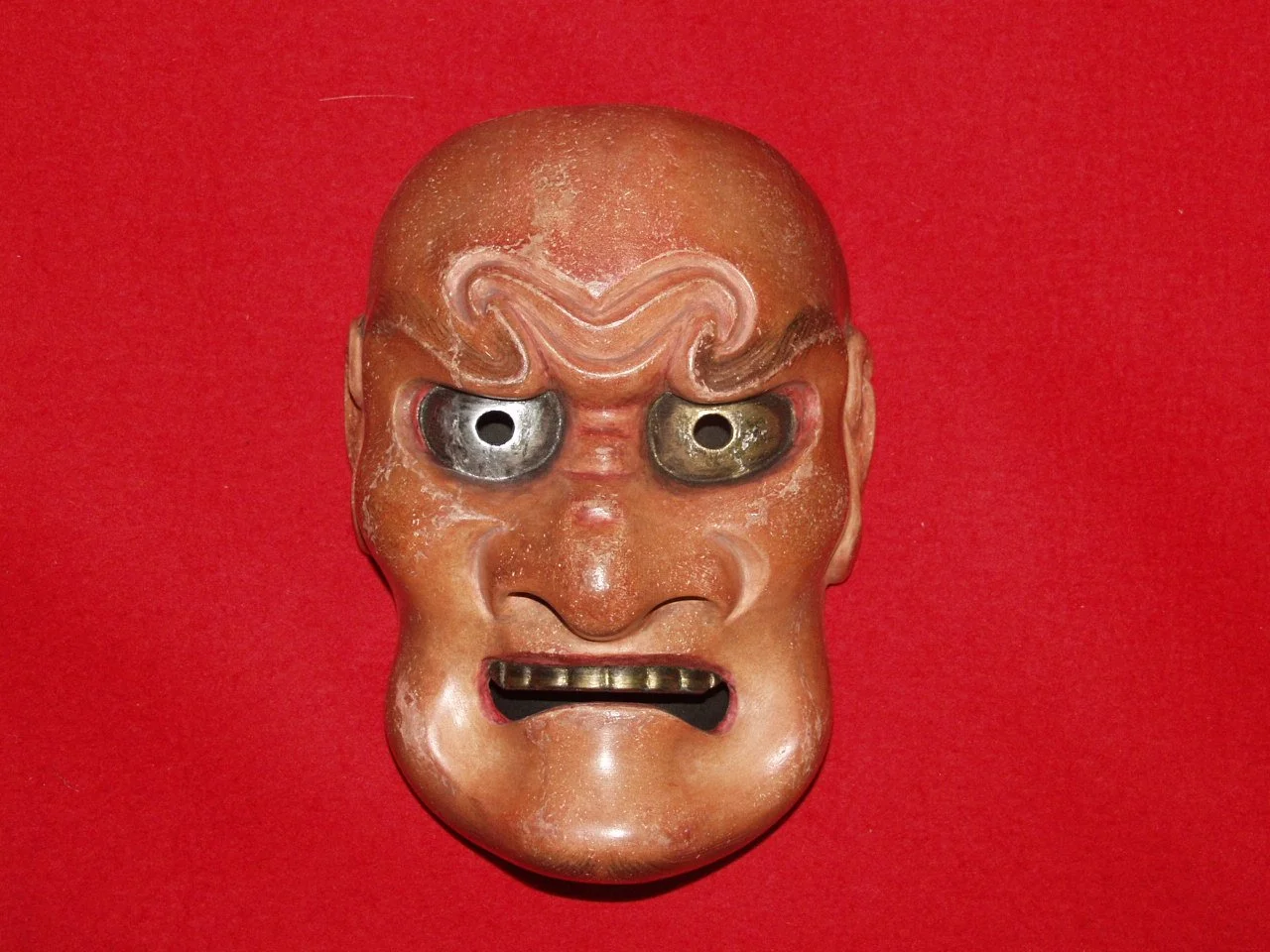

“John Davies has studied Noh in Japan. He directed Rakiura and plays the main character. He also carved the two masks that indicate the distinction between the two ‘halves’ of the story and the transformation of the character. He impresses with each achievement.”

The Dazzling Night

The second New Zealand Noh play production was The Dazzling Night, A Noh play about Katherine Mansfield, by Rachel McAlpine. This play is discussed in a conference paper from 2006 titled; Meeting the Dead on Stage: Noh Theatre and its Solution.

In this paper, I write;

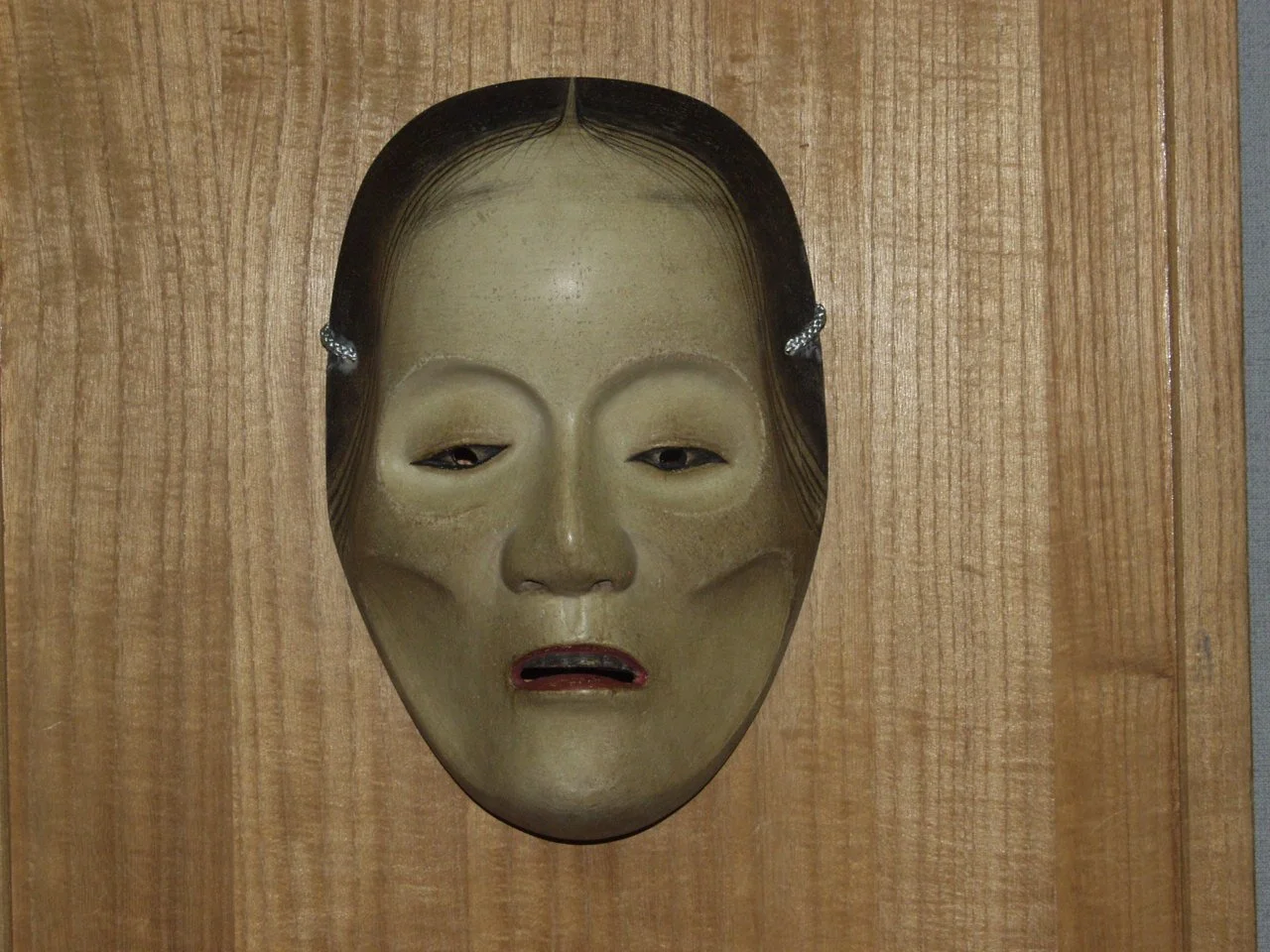

As I take soft steps to place myself upon the stage, I become the final stroke of colour in a brilliant painting. Mental paintings are prompted by the atmospheric lights, the dim shadows, the emptiness of the stage, and the silence. Then the shrill flute, as it summons the presence, calls the spirit to come be with us. The eerie cry of the drummers punctuating the stillness, ending the silence, and beginning it again. Mental pictures built by the mercurial writing of Katherine Mansfield, images and feelings conjured into the mind of the reader, brought to the theatre, associated with the name, living in the mind’s eye of the audience. I step onto the hashigakari, the bridgeway from the spirit world to the quick. Guided by the flute and the urgency of spiritual need, the elaborately robed and masked figure hovers before the audience.

“Who are you?” Asks the waki, Sir Harold Beauchamp, Katherine’s father.

“I am Katherine”, the shite sings in reply.

I am Katherine.

Image credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Eph-Post02121

The Blue Shawl

My work in this way I call Kapa Haka Noh, and it is continuing with new plays being developed. The important thing is collaboration.

This performance was dedicated to the memory of Tuaiwa (Eva) Rickard (1925-1997) and those people who were arrested at the Raglan golf course on the 12th of February 1978. Those 17 were charged with trespass, a charge that was subsequently dismissed in court.

Many years ago, a woman named Old Woman Bear, an indigenous Cree Indian and leader of her people, was given a blue shawl by her father to commemorate her graduation from university. Later on a visit to Aotearoa, as an expression of love and support, Old Woman Bear gave this shawl to a Māori woman. Five years later Old Woman Bear once again came to Aotearoa to strengthen friendships and lend support to Māori people in their struggle for indigenous rights. Upon visiting Eva Rickard one evening, she saw a photograph of Eva wearing the same Blue Shawl. She asked about it, and Eva said that it had been given to her; that it was her favourite and she wore it often with an appreciation for its colour, warmth and protective quality; she then went to the cupboard, took it down and showed it to her. Old Woman Bear never told her at that time that it had once been hers.

When Eva passed away, and her whanau were gathering stories about her life, Old Woman Bear wrote to them and told them of the Blue Shawl and how it had been passed from woman to woman, each gaining strength and shelter from its proud colour and protective spirit. Upon her last visit to Aotearoa, the whanau of Eva returned the shawl to Old Woman Bear, the circle complete. When they handed it to her, she said, “It smells the same as the day my father gave it to me, all those years ago”.

This Blue Shawl is surely a symbol of generosity, respect, loyalty and the spirit of shared struggle that brings mutual victory. This is my attempt to formulate this spirit into the form of a Noh Play, which for me is the true theatrical expression of spirit. I wish to express my gratitude to Angeline Greensill, who has with generosity and humour, guided us to a place where we could work together.

My sincere thanks to Waikato University Cultural Committee for their support.

Photo Credit: Tairawhitiroa

Whetu Silver, John Davies, Tema Fenton

Costume pattern design by Cheri Waititi & printed by Ali Davies

Karakia in preparation for performance University of Waikato 2008

Kongoh School of Noh, Kyoto

I would like to introduce my Noh Sensei, Udaka Mishishige (1947-2020) of the Kongoh School of Noh, Kyoto. We first met in 1984 and he has remained a friend and inspiration since. The International Noh Institute was foundered by him and his colleague Rebecca Ogama Teele. Becky remains a friend and valued teacher.

The video following this is “The World of Noh,” a video featuring excerpts from the Noh Tsunemasa with Udaka Sensei’s son Udaka Tatsushige in the Shite role.

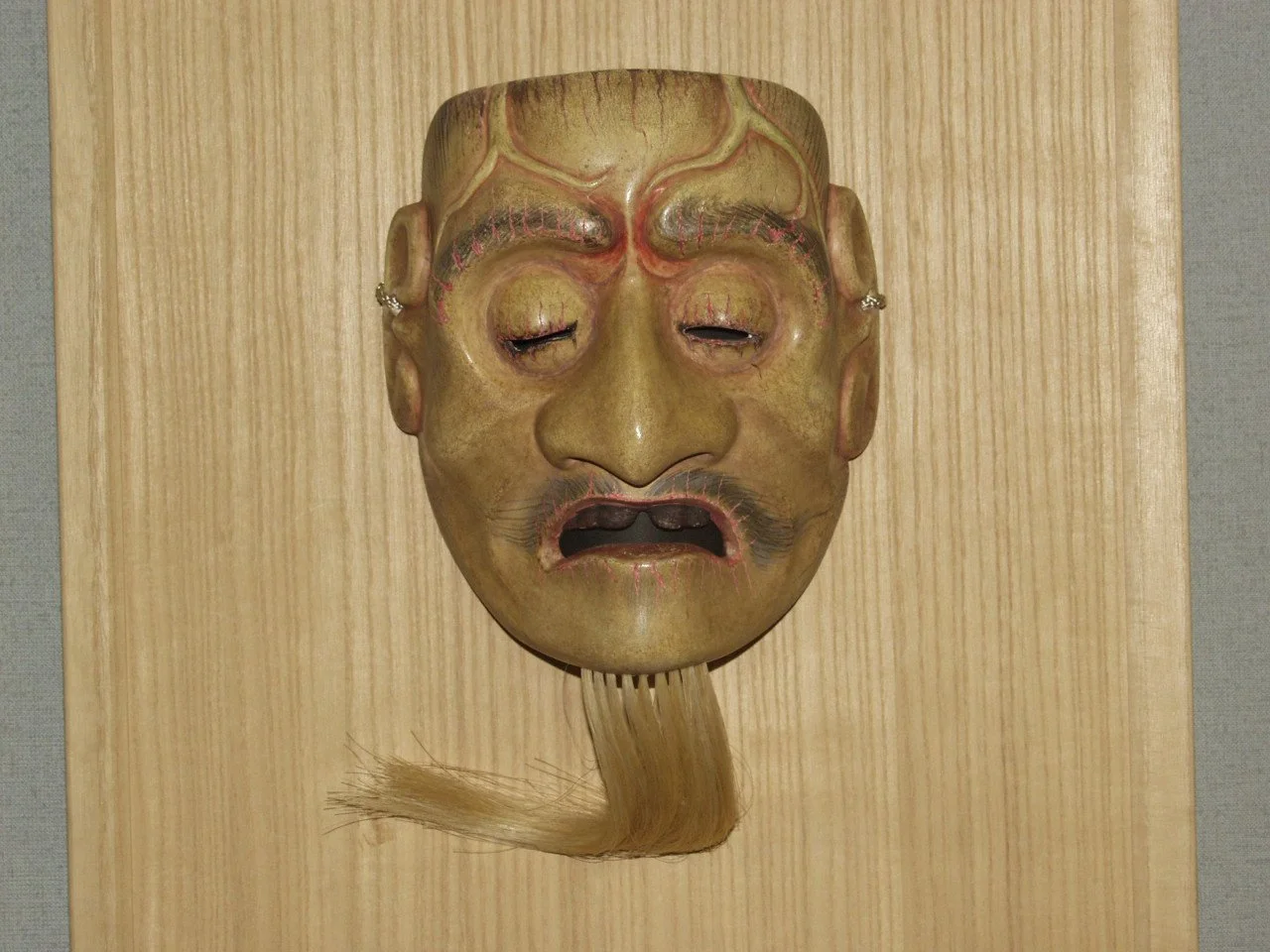

Noh Mask

I visited Kyoto in the spring of 2007 to celebrate the birthday of Udaka Sensei with performances and a sharing of our lives. We discussed a play he has written called Genshigumo: The Atomic Cloud. In this play, he used several masks that students had not completed, many of them abandoned and of strange expressions. These became an unconventional addition to a Noh play and were the spirits of those who perished in the atomic blast. This additional chorus inspired me to take such liberties myself and led to the mobile kapa haka chorus in The Blue Shawl.